Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s first web series, an artful and overwrought female-led period drama, is crammed with everything that the director’s big-screen ventures are known for. It has massive and lavish sets, visual grandeur, intense emotions, stylistic flamboyance, sustained musicality and striking performances. Is there more? Yes, there is.

Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar reimagines 1940s Lahore and its red-light district in a manner far less intent on accuracy of detailing than on the overall effect of the enterprise. The show has passages of effulgent beauty. It also occasionally slides into tonally static, cinematically sterile stretches. But in the ultimate analysis, its strengths far outnumber its downsides.

Bhansali is the creator, co-writer (with Vibhu Puri), editor and music director of the extravagant eight-episode Netflix show that economizes on nothing at all. It is filmed all the way like the widescreen spectacle that it is intended to be.

Based on an original concept by Moin Beg, Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar places the daily struggles of the fabled but exploited courtesans of Lahore alongside a rapidly escalating war for independence waged by a band of underground rebels.

Bhansali tempers his maximalist methods with restraint. The series is a celebration of as well as a lament for a house of spirited courtesans yearning for dignity and liberty in the tumultuous final years of the British Raj, an era marked by the rapidly declining clout of the nawabs who were the chief patrons of the nautch girls of Heeramandi.

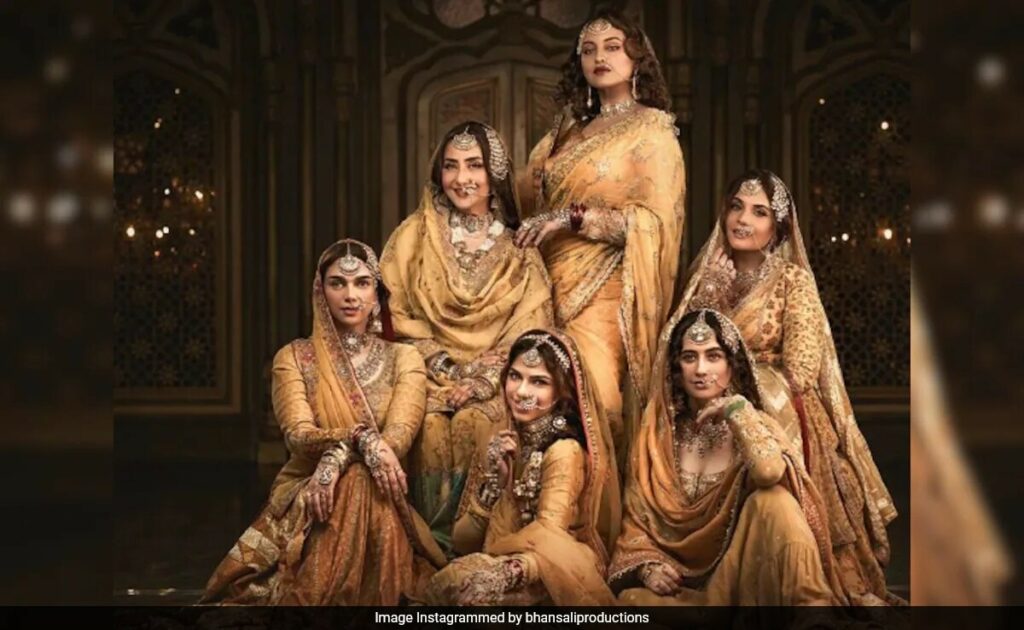

Bhansali draws the very best out of the six principal members of the cast – Manisha Koirala, Sonakshi Sinha, Aditi Rao Hydari, Richa Chadha, Sanjeeda Sheikh and Sharmin Segal.

Manisha Koirala, returning to a Bhansali project 28 years after Khamoshi: The Musical, Sonakshi Sinha, coming off the triumph of Dahaad, embody two feisty women who denote the two principal poles of the a battle to control Heeramandi.

But it is Aditi Rao Hydari, cast as an epitome of sedate grace and refinement, who gets a wider emotional spectrum to straddle. Sharmin Segal, playing an innocent but gifted young woman who wants to escape her destiny, has her moments, as does Sanjeeda Sheikh as a scarred woman at the receiving end of the bitter power struggle between forces much stronger than her.

Bhansali is just as impressive in the way he harnesses the potential of the supporting actresses – notably Farida Jalal, Nivedita Bhargava, Jayati Bhatia and Shruti Sharma – to conjure up a sophisticated, if self-consciously stylised, portrait of a tumultuous time and a unique culture trapped caught in a maelstrom triggered by the vagaries of history and the myopia of self-serving men.

The male cast – the actors play marginal figures who call the shots in the lives of the courtesans or control the law-and-order machinery in the city – is far less effective. It includes Fardeen Khan, making a comeback after a 14-year hiatus, and Shekhar Suman, who, too, has been missing from the screen for years.

The roles that Khan and Suman play – nawabs who have the tawaifs of Heeramandi as mistresses in a give-and-take relationship teetering on the edge of desire and distrust – are peripheral to the larger drama.

Three other male actors – Taha Shah, playing a well-connected and strategically pliant aristocrat’s London-returned son who rebels against his father and the British, Jason Shah as a brutal British police officer and Indresh Malik as a foppish, wily mediator between the nautch girls and their fickle benefactors – are accorded greater play. They make the most of it.

One of Heeramandi‘s patrons (played by Adhyayan Suman, who is also cast as the younger avatar of the character essayed by Shekhar Suman), demonstrates that the attention and riches that a debauched nawab showers on a tawaif, Lajjo (Richa Chadha), are not permanent. They are part of an easy to violate Faustian contract.

It isn’t just devious outsiders who cause misery. The nautch girls themselves are equally capable of inflicting pain on each other with bursts of envy and acts of betrayal that stem from the need for acceptance and self-assertion. The Heeramandi courtesans are a closely-knit community – most of them are related by blood – but that does not stop them from ceaselessly exchanging verbal and psychological barbs.

The series plays out predominantly in two mansions that stand opposite each other in the disreputable neighbourhood frequented by the powerful and the wealthy. One is Shahi Mahal (which translates to royal palace), where a seasoned Mallikajaan (Manisha Koirala) is the undisputed queen.

The other, Khwabgah (meaning “house of dreams”), is a much-coveted mansion into which the younger Fareedan (Sonakshi Sinha) moves after relocating from Benaras. Fareedan, the only daughter of Mallika’s dead elder sister, has a score to settle with the denizens of Shahi Mahal.

Delusions of royalty and the lure of dreams sustain Mallikajaan and her likes. Dreams, as one of the women says, is their worst enemy. We can only see them but never realise them, she adds. It is the courtesans’ perennial oscillation between hope and despair that lies at the core of the drama of their unstable lives.

Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar sustains its spotlight on the women even as it liberally sprinkles its sweeping, overflowing canvas with intimate moments of love, jealousy, deceit and rebellion and with unfolding processions, street clashes and cases of custodial torture that leave a trail of blood and unspeakable horrors.

At once seductive and sad, poignant and prevailing, the tawaifs dwell in the heart of Lahore but are doomed to languish as dispensable objects of fancy on the fringes of a society controlled by nawabs on the brink of oblivion and ruthless British officials desperately clinging on to their authority on an increasingly restless colonised people.

The dice is loaded against the courtesans, but they are the ones who emotionally control the moneyed men on whom they depend for their upkeep. But how long can they protect their shaky turf and keep the nawabs in their thrall?

As the rumblings of the swadeshi movement spill into Heeramandi – Bibbojaan (Aditi Rao Hydari) and Alamzeb (Sharmin Segal), Mallika’s two daughters, are drawn into the freedom struggle, one directly, the other inadvertently – the courtesans are caught in a cleft stick. They can either side with the nawabs who lack the courage to resist the British or throw their lot with the freedom fighters.

The ornately mounted Heeramandi might at first flush appear to be a conventional SLB endeavour. It presses pretty images couched in music and poetry into the service of an account of an obscure and fictionalised chapter of the subcontinent’s history. That it does so with consistent competence is only to be expected.

The cinematography is credited to four DoPs – Bhansali’s frequent collaborator Sudeep Chatterjee along with Mahesh Limaye, Huenstang Mohapatra and Ragul Dharuman – and the production design is by Subrata Chakraborty and Amit Ray. Both teams of technicians make flawless contributions to the show.

There is, however, more to the series than the blindingly, and distractingly, sumptuous means that Bhansali employs. There is a significant takeaway from the way Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar frames the fight for India’s independence as a movement that defied the Crown’s divide and rule policy.

Hindus and Muslims walk shoulder to shoulder as they plot strikes against the British. Religious identities do not divide the fighters. Their commitment to azaadi unites them. In the climate that obtains in today’s India, the espousal of the subcontinent’s entrenched syncretism is a noteworthy thematic strand that should not be lost in the hypnotic glow of the glitzy Heeramandi universe that Bhansali conjures up.

Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar isn’t all pomp and show. Both nostalgic and elegiac, it contains a core that is worth more than all the glitter and glory of its packaging.