Chinese President Xi Jinping is trying to win friends and influence people in Europe during his first trip to the continent in five years. As Beijing tries to recalibrate its broader foreign policy posture, Europe is the first port of call at a time when tensions with the West have been ratcheting up in multiple domains. For the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), steadying the Chinese economy is the foremost priority, and towards that end, having a stable relationship with Europe is key when power contestation with the US is unlikely to subside any time soon. Europe’s role as a balancer is critical for China to continue to shape the global balance of power in its favour.

Though there have been some tentative moves in the positive direction in the US-China relationship in recent weeks, the US Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, was categorical at the end of his three day visit to China that Beijing was “helping fuel the biggest threat” to European security since the Cold War and that Washington would act if China did not stop supplying Russia with items used against Ukraine on the battlefield. It is no wonder that for China, Europe is seemingly a simpler alternative at this stage than managing its fraught ties with the US.

Divisions Within Europe

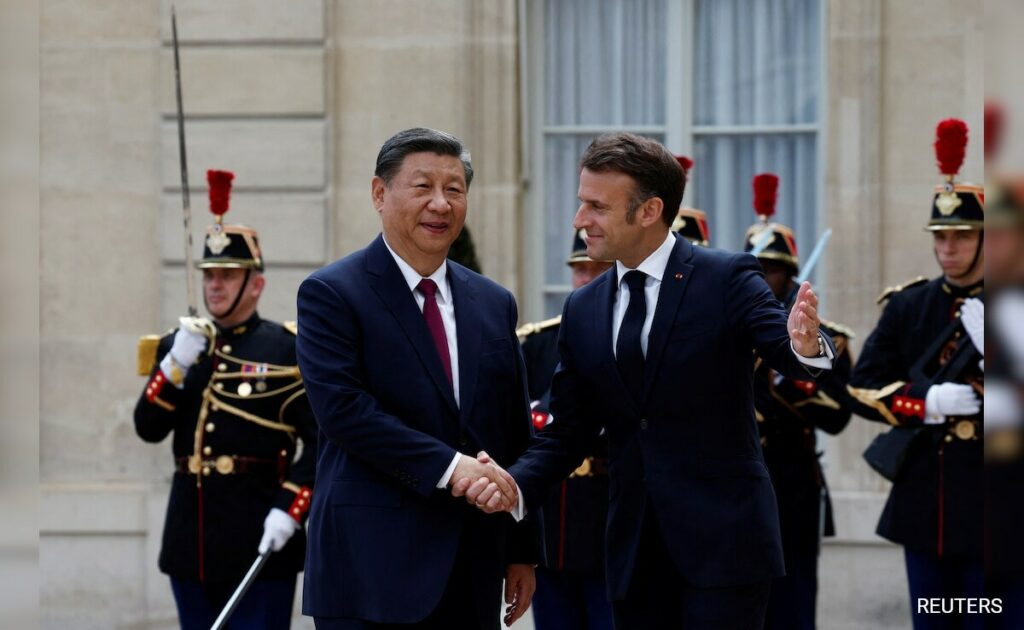

This week’s visit of Xi is choreographed to send a clear message to the West that China is today positioned not only to engage with traditional powers like France but has newer partners like Serbia and Hungary, which have traditionally been allies of Moscow but are now enamoured of Chinese economic prowess. In France, there was nothing that Xi offered to try to change the antagonistic posturing. He made it clear that China opposes “using the Ukraine crisis to cast blame, smear a third country and incite a new Cold War”, while announcing that he supported the French president’s call for an “Olympics truce”. Beijing recognises well that this is an exercise in futility and wishful thinking on the part of Paris, so it finds no harm in mentioning aspects of policy, if only to massage France’s ego.

With both French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz trying to endear themselves to Beijing, the divisions within the European Union on China stand out starkly. This despite the fact that there has been a dramatic change in perceptions about China in Europe. What was once considered a binding factor – trade – has today emerged as a major bone of contention. Both Europe and China have invested heavily in each other’s markets, but barriers to market access and investment restrictions persist. Europe has expressed concerns about fair competition, state subsidies, and the protection of intellectual property rights in China, while China seeks greater access to European markets and technology transfer.

Chinese Investments Are Important For Some

European countries have criticised China for its lack of reciprocity in trade and investment relations. While European markets are relatively open to Chinese investment, access to the Chinese market remains restricted for European companies, with concerns about unfair competition and forced technology transfer. Europe is wary of China’s growing technological capabilities and its potential implications for cybersecurity. Concerns about Chinese telecommunications companies such as Huawei and their involvement in critical infrastructure projects have led some European countries to restrict or exclude them from their networks due to perceived security risks and potential espionage.

But parts of Europe continue with their outreach to China. Serbia’s ties with China have accelerated in recent years, though it continues to seek an entry into the European Union. Last year, the two nations inked a free trade pact, bolstering their “comprehensive strategic partnership” established in 2016 during Xi’s prior visit to Serbia. Following Belgrade, China’s president will head to Budapest, where Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has emerged as Xi’s staunchest ally among EU leaders.

Chinese investments play a significant role there as well, with projects like the electric car giant BYD’s factory allowing Orban to challenge the EU consensus on issues over a range of subjects. The Hungarian government has tried its best to sweeten the deal for Chinese investments, and a high-speed railway seeking to connect Central Europe to the ports of Thessaloniki and Piraeus is a case in point. Xi’s visits to Serbia and Hungary this week also underscore the enthusiasm for China in certain parts of Europe.

Competing Interests And Values

These divisions within Europe over China are only going to grow in sync with a spectrum of interests and concerns among its member states. While some nations prioritise economic cooperation and view China as a crucial trading partner and source of investment, others are becoming more apprehensive about Beijing’s growing influence, particularly regarding human rights, disinformation, and geopolitical ambitions. Additionally, debates over infrastructure and connectivity, technology standards, 5G networks, and supply chain security further underscore the discord. These divisions within Europe illustrate the complexities of navigating relations with China amidst competing interests and values.

As geopolitical tensions between the US and China become starker, Europe’s space to manoeuvre will only shrink and the ability of Beijing to exploit the cleavages within the West will also increase.

For New Delhi, Europe has emerged as an important partner sharing convergent geopolitical worldviews. A strong united European voice in the global order is important for managing the turbulence in the balance of power. India would be hoping that the divisions within Europe on display during Xi Jinping’s visit don’t translate into a weaker strategic profile. For this, it will be critical that India’s own engagement with Europe remains serious and forward-looking.

[Harsh V. Pant is a Professor of International Relations at King’s College London. His most recent books include ‘India and the Gulf: Theoretical Perspectives and Policy Shifts’ (Cambridge University Press) and ‘Politics and Geopolitics: Decoding India’s Neighbourhood Challenge’ (Rupa)]

Disclaimer: These are the personal opinions of the author