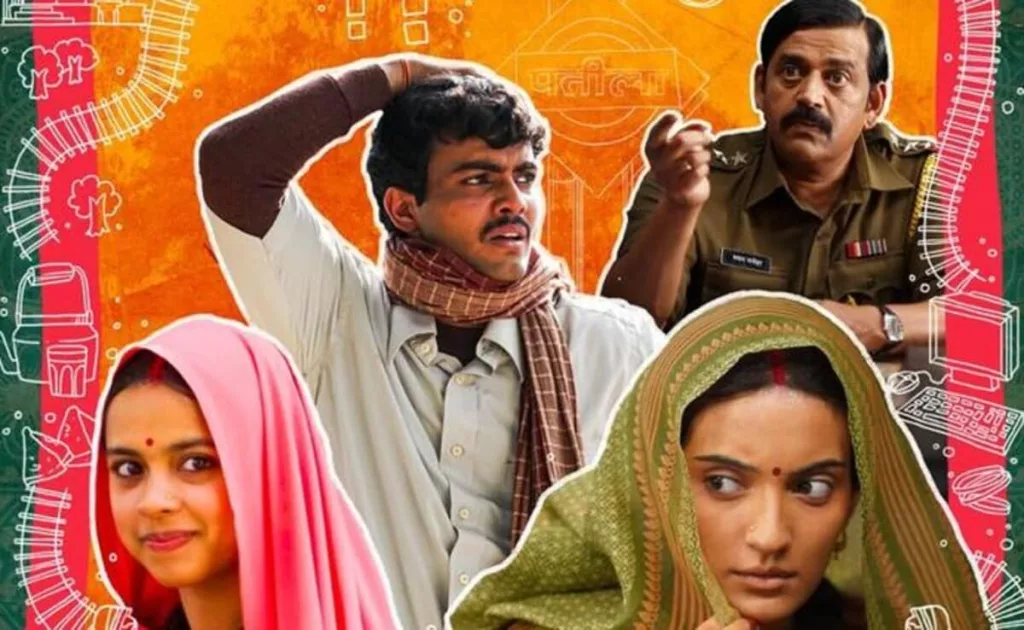

We may all have been hoping against hope for happier tidings, but it was no surprise at all that Laapataa Ladies fell short of the shortlist of 15 titles that will be considered for nomination in the International Best Feature Film category at the 97th Academy Awards. The elimination is, however, no reflection on the intrinsic merits of Kiran Rao film.

Laapataa Ladies had much going for it, but it simply wasn’t in the right place at the right time. It lost its way because it was up against a bunch of international festival circuit favourites that had a head start from the moment they were named as contenders by their respective countries.

I’m Still Here, the Brazilian entry, won the best screenplay prize in Venice. Ireland’s hip-hop musical Kneecap and the Czech historical drama Waves were audience award winners at Sundance and Karlovy Vary respectively.

We are not even talking here about Jacques Audiard’s Emilia Perez or Mohammad Rasoulof’s The Seed of the Sacred Fig, a Farsi-language that Germany’s official entry.

Barring Emilia Perez, a French production set in Mexico and filmed in Spanish, and The Seed of the Sacred Fig, none of the aforementioned films were preceded by the sort of global buzz that Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine as Light was. But the all-male, fossilised Film Federation of India (FFI) jury ignored the Cannes Grand Prix winner on the risible ground that it wasn’t “Indian enough”.

It was a gilt-edged opportunity lost and not for the first time. Contrast the AWIAL snub by FFI with the arc of British-Indian filmmaker Sandhya Suri’s social commentary-laden, Hindi-language police procedural Santosh, the UK’s official Oscar entry.

Sanotsh was found British enough to be granted the honour of being a rare UK contender in the non-English language film category at the Oscars. That the India-set drama starring Shahana Goswami and Sunita Rajwar in the Oscar shortlist is proof that cinema is a language unto itself that transcends barriers of language, culture and milieu.

The selection process to pick India’s entry for the Best International Feature Film Oscar has been the butt of ridicule for years. Justifiably so. The wise men (and occasionally women) who deliberate upon which film will represent the world’s largest movie producing nation at the Oscars always find ways of getting it horribly wrong.

They outdid themselves in 2013, the year they bafflingly plumbed for Gyan Correa’s Gujarati film The Good Road at the expense of Ritesh Batra’s The Lunchbox, the Irrfan Khan-Nimrit Kaur-Nawazuddin Siddiqui starrer that began its journey in Cannes and travelled the world thereafter.

In 2012, too, FFI tied itself up in knots. It picked Anurag Basu’s Barfi! as India’s official Oscar entry. The film, expectedly, had no chance of ever being in the reckoning in a year in which Asghar Farhadi’s piercing marital discord drama A Separation took home the Oscar.

Last year S.S. Rajamouli’s action extravaganza RRR was all the rage globally and was tipped to be a strong contender for the Best International Feature Film Oscar. FFI chose the Malayalam-language survival drama 2018 instead. Many of those who championed RRR’s cause felt that the selection was inexplicable and it stymied any chance India had of a fair shot at an Oscar.

In all these years, India has managed to snag only three nominations in the Best International Feature Film Oscar category – in 1957 (Mother India), 1988 (Salaam Bombay!) and 2001 (Lagaan). Mother India reportedly lost by a whisker – one vote – to Federico Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria.

It was also suggested without any official corroboration that Lagaan, too, ran the eventual Oscar winner of 2001, Danis Tanovic’s No Man’s Land, tantalisingly close.

Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay!, winner of the Camera d’Or in Cannes in 1988, ranks among the better choices that India has made. The film lost to Bille August’s Pelle the Conqueror in a year that also had Istvan Szabo’s Hanussen and Pedro Almodovar’s Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown in the running.

Until the 1970s, India’s Oscar entry selectors seemed to be aware of what they were doing. The films that they chose included Satyajit Ray’s Apur Sansar (1959), Mahanagar (1963) and Shatranj Ke Khiladi (1978), M.S. Sathyu’s Garm Hawa (1974) and Shyam Benegal’s Manthan (1977). None of them went the distance but they were not embarrassments either.

The selection process plummeted precipitously and assumed farcical proportions in the 1990s, hitting its nadir in 1998. That year India sent the S. Shankar potboiler Jeans to the Academy Awards because Ashok Amritraj was the film’s lead producer. The calculation of the jury was that because Amritraj was based in Los Angeles and enjoyed considerable clout in Hollywood Jeans would stand a chance of muscling its way through.

They forgot that no matter how much trash is pushed, it can never turn into gold dust. Jeans was S. Shankar’s second film in three years – the first was the Kamal Haasan vehicle Indian (1996) – to be chosen as India’s official Oscar entry.

In the wake of the excitement that the Oscar nomination for Lagaan generated, it was felt in certain quarters that the time had finally come for India to up the ante and look for greater glory at the Academy Awards. But the foot in the door proved to be a flash in the pan.

In 2002, the year after Lagaan’s memorable run at the Academy Awards, the FFI, in its wisdom, nominated Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Devdas instead of Mani Ratnam’s Kannathil Muthamittal (A Peck on the Cheek) or Buddhadeb Dasgupta’s Mondo Meyer Upakhyan (A Tale of a Naughty Girl). Not that either of snubbed films would have earned a nomination, let alone won, but they had far greater cinematic potential.

Pretty much the same story was repeated in 2007. India’s official Oscar entry that year was Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s Amitabh Bachchan-led multi-starrer Eklavya – The Royal Guard. Among the titles that FFI could have chosen ahead of Eklavya was Deepa Mehta’s Water, the third film of her Elements trilogy.

To be fair, there have been years when FFI backed the most deserving horse and raised hopes of a breakthrough. In 1994, Shekhar Kapur’s international breakout Bandit Queen earned the nod. In 2015, it was the turn of Chaitanya Tamhane’s critically acclaimed festival hit Court.

The very next year, India sent Vetrimaaran’s gritty Visaranai to the Oscars. In 2017, FFI got it right once again, choosing Amit V. Masurkar’s Newton, which had premiered early in the year in the Forum section of the Berlin Film Festival.

In 2021, another Tamil film, debutant P.S. Vinothraj’s Koozhangal (Pebbles), winner of the Tiger Award at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, made the cut. But small films with limited resources often lack the means to lobby hard enough to attract the attention of the Academy members.

It admittedly isn’t a level playing field, but had the FFI had a better idea of how to go about things India’s wait for a Best International Feature Film Oscar might have ended this year.